We are ‘On Your Side’

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was a litmus test for existing racism and discriminatory practices. A research report from the United Kingdom showed that, ‘according to U.K. police data there was a rise of 300% in hate crimes towards ESEA people in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the same period in 2018 and 2019’.[1] However, this number tells us only a fraction of the larger picture of structural racism.

In this article, we discuss how the movement against racially motivated hate crime[2] started in the UK, the role of ESEA organisations in sustaining it, and aligning issues and activisms within the movement. We highlight the role of our UK partner Southeast and East Asian Centre (SEEAC) within this movement.

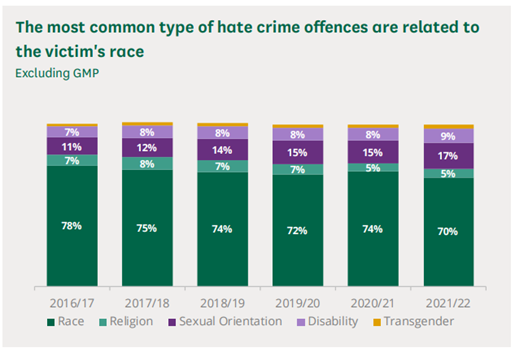

Image 1: Racially motivated crime rate out of all hate crimes. GMP= Greater Manchester Police Source

Movement: A unified front that upholds diversity

The movement in the UK against hate crimes grew organically after the increase in and reporting of these incidents in 2020. The movement was initially mobilised and led by youth, mostly representing second-generation, mixed-heritage groups. It was communicated in English primarily on social media like Twitter and Instagram. Some of the steps to demand accountability from the state started with a letter to the UK government to initiate a public inquiry into this matter. SEEAC joined the movement, highlighting the experiences of the migrant ESEA communities well-acquainted with the multiple marginalisations and systemic racism embedded in the UK immigration system faced.

SEEAC grounded the movement that demanded protection for ‘British East and Southeast Asians’ to alter its articulation to include all ESEA migrants regardless of their citizenship or immigration status. It also demanded a shift in the discourse where the ‘solution’ of reporting hate crimes to the police was reimagined to include options for those who needed support but did not necessarily want to engage with law enforcement. This took into consideration cases of migrants whose visas were tied to their partners or employers who could very well be the perpetrators. Due to the limited immigration routes and fear of cancellation of their visas, these community members may fear involving the police. At the same time, the limited options and restrictive policies put migrants at higher risks of abuses.

Not discounting the value of reporting, SEEAC argued for measures for informed decision making and for protecting the privacy of the victim’s identity unless stated otherwise. This also made room for other forms of violence that go beyond the visibility of verbal and physical abuse that have sensational elements and is reported by the media. This approached opened up conversations around psychological and subtle forms of violence and discrimination against ESEA communities. SEEAC overcame the limited accessibility to knowledge for its community members by translating materials into several Asian languages. As the movement contracted in 2021, SEEAC and its allies developed a common language around the issue to start a support service called ‘On you Side’.

Image 2: Limited visa routes to the UK

We are ‘On Your Side’

On Your Side was established to support anyone in the UK who is part of an East or Southeast Asian community and witnesses or experiences racism or any form of hate crime. It is run by a consortium of 15 members, mainly East and Southeast Asian community organisations. Three are lead organisations and the other 12 are in support roles that offer casework, advocacy and outreach. SEEAC is one of seven organisations providing casework support. On Your Side is a third-party reporting service, funded by but independent of the UK government. It is a 24-hour confidential service that operates in 5-6 Asian languages. Through their outreach work, they encourage the sharing of experiences of discrimination and hate so that they can offer help and also collect data in order to take preventative steps. As casework advocates, SEEAC provides long-term assistance to community members with peer support, one-on-one support, immigration and welfare-related assistance, and mental healthcare. This is a small subset of SEEAC’s work on ensuring the socio-economic and psychological wellbeing of members of ESEA migrant communities.

According to a new draft code of practice laid before Parliament in March, the police will only record non-crime hate incidents (such as verbal or online abuse, insults or harassment) ‘when it is absolutely necessary and proportionate and not simply because someone is offended’. The measure is put in place to protect people’s fundamental right to freedom of expression as well as their personal data. This code of practice bears the dangers of ‘normalising’ forms of violence and relying on the judgement and subjectivity of the police. A better approach would be to work on the underlying issues of prejudices and biases of hate crime through community crime prevention, changing public perceptions, and altering the public discourse by careful messaging by media and public duty bearers. It is not a mere coincidence that hate crime spikes around catalysing events like the Brexit referendum, terrorist attacks, COVID-19, or the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. Services like On Your Side become more urgent - for both reporting and as a database to push back against policies like this code of practice.

Key Takeaways

As a community-based organisation, SEEAC, along with the other members of the consortium, was able to widen the reach of this service to those with limited access to healthcare and resources. The service prioritises hate crime because data shows that ‘victims of hate crime were more likely to be impacted emotionally and psychologically following a crime than victims of all crime’. It also emphasises the role of resources available to a community-based organisation that often need to respond more fastidiously to coordinate and advocate for change and cannot rely on short-term, project-based funds. Additionally, organisations that represent ‘affected communities’ must be involved in policy decisions because they can bring forth experiences that will otherwise be left out. It has the potential to break away from the rhetoric of ‘deserving minority’ vs ‘intruders’, which perpetuates exclusion.

Ultimately, even amongst community members, it takes trust-building, time, and persistence to open up and share negative experiences. A second-generation Vietnamese youth will perceive violence or hate crime differently than, for example, a Vietnamese irregular migrant nail salon worker. The colonial, polarising ‘us vs them’ lens is not the approach to overcome this. There is a need to engage a level of political and economic history for these two experiences to reconcile.

Written by Srishty Anand (GAATW-IS), Luisa Pineda (SEEAC) and Mariko Hiyashi (SEEAC) with editorial inputs from Borislav Gerasimov

[1] ESEA refers to people from East and Southeast Asia in the UK.

[2] Hate crime in the UK is defined as, ‘any criminal offence which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice towards someone based on a personal characteristic’. The five centrally monitored strands of hate crime are: race or ethnicity, religion or beliefs, sexual orientation, disability and transgender identity.