Borislav Gerasimov, 21 January 2020

A slightly modified version of this blog first appeared on Beyond Trafficking and Slavery

The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) was founded in 1994 by a group of feminists and women’s rights advocates from, mostly, the Global South. As students, activists, asylum seekers, or migrants in the Global North, they had witnessed the struggles of their compatriots with much less privilege than their own. And as volunteer caregivers, translators, interviewers, and advocates in law courts, GAATW’s founding mothers had heard the stories of working-class migrant women who had undertaken journeys in search of better livelihoods.

Typically, women narrated stories of difficult situations: of the broken promises of agents/recruiters, unbearable working conditions, and financial destitution. Their stories, hard as they were to hear, testified to the women’s courage, enterprise, and determination and challenged the stereotype of ‘the victim of trafficking’ prevailing in the Global North.

Trafficking and sex work

GAATW has always been an ally of the sex worker rights movement. As feminists and human rights activists, our founding mothers thought it natural to support self-organising among this group of women. In the beginning, some were uncomfortable with the idea that ‘sex work is work’. However, their repeated interactions with individual sex workers and fledgling collectives forced them to question their middle-class mores.

A few months ago, I met a feminist activist in Thailand who now works in the field of sexual and reproductive health and rights. She explained that she had been close to GAATW since the very beginning, and that back in the 1980s she had wanted to rescue Thai sex workers in the Netherlands. To her surprise, they had told her they didn’t want to be rescued. They did not mind trading sex for money but wanted to earn more and work in better conditions. If she could help them with that, she was welcome. This and other similar interactions changed her views of sex work and sex workers.

When she told me this story, I remembered something that Lin Lap Chew, one of GAATW’s founding mothers, wrote in Trafficking and Prostitution Reconsidered about the evolution of her own views at the time: “I [was] convinced that I was not against the women who worked as prostitutes, but that the patriarchal institution or prostitution should be dismantled”, she wrote. “But soon I was to learn, through direct and regular contact with women in prostitution, that […] the only way to break the stigma and marginalization of prostitutes was to accept the work that they do as exactly that – a form of work.” She ended with the observation that “The personal struggle for me was to overcome the mainstream moral hypocrisy into which I had been socialized.”

Regular conversations with sex workers made both of these committed activists change their view from ‘prostitution is patriarchal violence against women’ to ‘sex work is work’. That doesn’t always happen and I’ve long wondered why. Why does speaking with sex workers change some people’s minds about sex work, but not others’? I don’t have the answer, and probably never will. Perhaps for the GAATW founding mothers, a paraphrase of this old Latin saying held true: ‘Kathleen Barry is my friend, but truth is a better friend (amica Kathleen Barry sed magis amica veritas)’.

Sex work as work, sex workers’ rights as workers’ rights

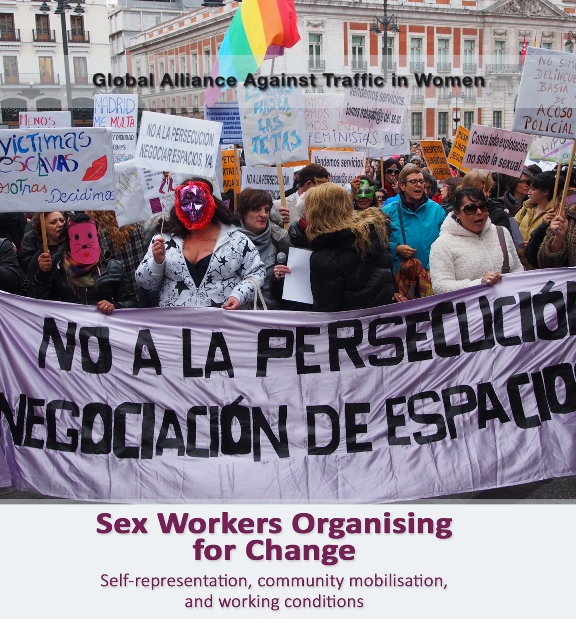

GAATW’s support for the sex worker rights movement stems from our conviction that women are better able to challenge power and bring about change when they organise to collectively analyse their situation. This is as true for sex workers as it is for Indigenous, Dalit, migrant or trafficked women, farmers, domestic workers, and hawkers. We are honoured to stand in solidarity with their struggles. We do not pretend to speak on their behalf and GAATW will never lead a campaign on decriminalisation. But we will support those who do.

That said, we do encourage our partners in the women’s rights, labour rights, migrant rights and anti-trafficking fields to engage with sex workers as part of the larger struggle for human rights and workers’ rights. Even people who despise sex work should agree that those in it should be free from violence and stigma. They should also agree that all workspaces should have decent working conditions, regardless of the nature of work. To wish anything else – to posit that sex workers should face violence, stigma, and abuse at work because their livelihoods raise moral questions – is an odd position to take. As a colleague from another organisation told me once, “I don’t have particular feelings about the garment industry. But I want the workers who make clothes to do so in good conditions”.

GAATW does not separate ‘trafficking for sexual exploitation’ from ‘trafficking for labour exploitation’ (or ‘sex trafficking’ from ‘labour trafficking’ as they say in the US) as most organisations do. When necessary we specify whether we are talking about trafficking in the sex industry, or in domestic work, or in construction, agriculture, fishing, etc. This may seem petty and unimportant but it’s not. Language shapes thought. Drawing a line between ‘sexual exploitation’ and ‘labour exploitation’ in itself suggests that sex work is not work. Anyone who agrees that sex work is work should avoid referring to different forms of trafficking in this way. In particular, American activists, journalists, researchers and others concerned with sex workers’ safety should absolutely stop using the term ‘sex trafficking’.

We follow the same strategy in our mutual learning and knowledge sharing work. Migrant and trafficked women’s stories are strikingly similar regardless of the sector in which they are exploited. They all speak of deceptive agents and brokers, limited freedom of movement, physical, psychological, and sexual violence at the workplace, as well as stigma upon return. The strategies that women use to resist and escape exploitation are similar too. Our mutual learning exercises have taught us that, for all the talk of the unique nature of the trade, exploitation in the sex industry isn’t unique at all.

It is well known that some migrant women working in, for example, domestic work, garment factories, or restaurants do sex work on the side to earn more money. Yet, trade unions and NGOs working on migrants’ rights, domestic workers’ rights, and garment workers’ rights see sex work and sex workers’ rights as something completely unrelated to their work and their communities. When we organise convenings for different stakeholders, we always invite sex worker rights groups. This strategy has led to some people recognising the common experiences of women working in different sectors and at least being more open to learning about sex workers’ struggles.

Advocating for the rights of sex workers to other groups is not an easy task. I often hear from our partners that they ‘don’t have a position on sex work’. I understand where this is coming from, but it highlights a gap in logic that often appears when talk turns to sex work. GAATW doesn’t have a position on many issues or groups of women. We don’t have a position on cooking or selling vegetables on the street, even though there are women who cook or sell vegetables all around us in Bangkok. Yet our instinct would always be to stand in solidarity with them and support them in their demands, whatever these are – for example, for the right to work where they can attract the most customers, maintain decent prices, and protect themselves against exploitative rents and corrupt government officials. These are the demands of all workers, including sex workers. Trade unions, women’s rights and migrants’ rights organisations should stand in solidarity with them.