Borislav Gerasimov

|

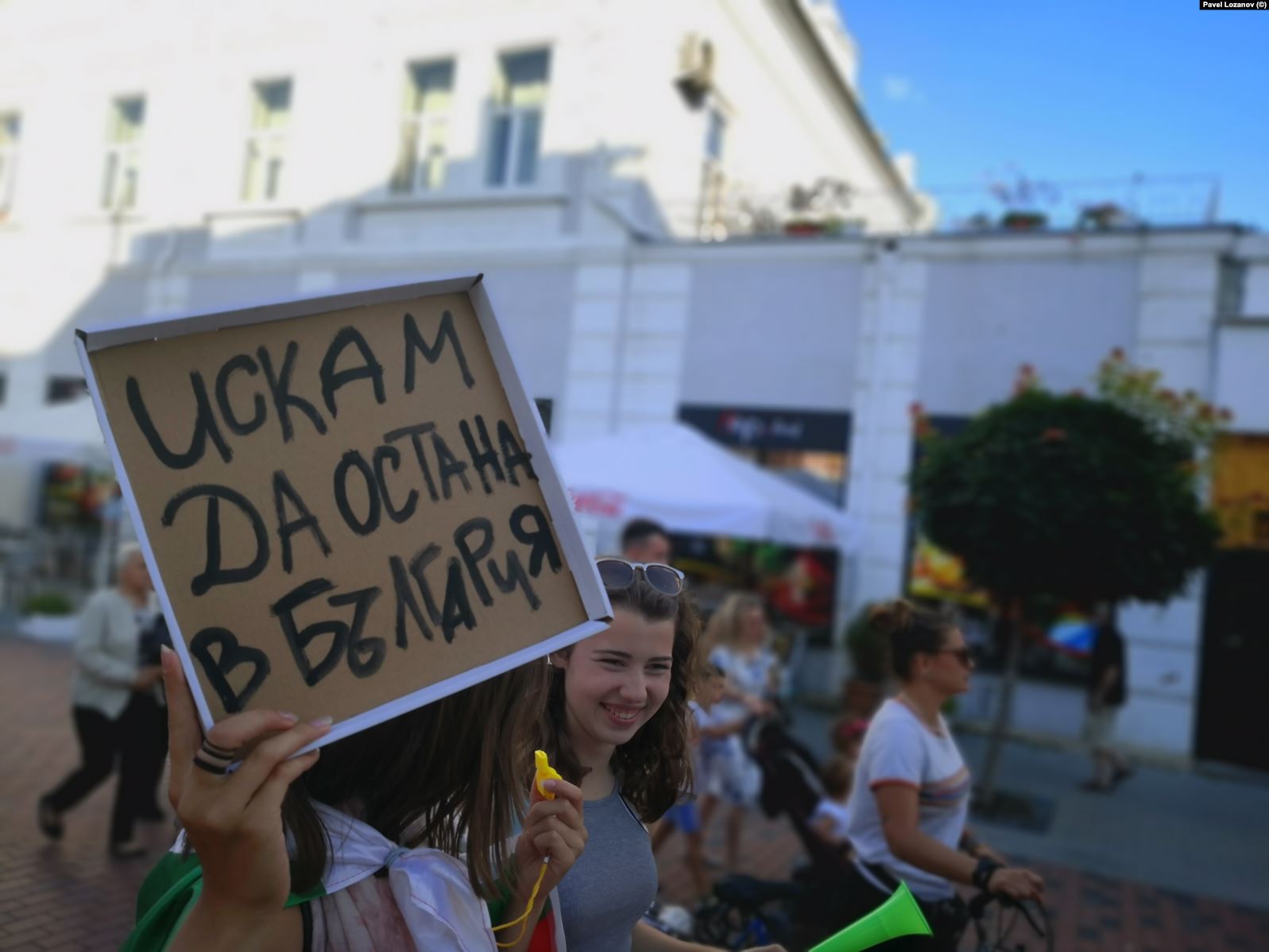

| (A young woman carries a sign that reads “I want to stay in Bulgaria” during a protest in Varna, 14 July 2020. Image: Pavel Lozanov / Svobodna Evropa) |

Bulgaria has been rocked by massive protests since early July, with tens of thousands of people out on the streets demanding the resignation of the Government and the Prosecutor General. People are angry about the wide-spread corruption and the increasing concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small oligarchy while one-fifth of the population lives below the poverty line. Personally, I don’t think the Government’s resignation will bring about the desired change – protests, oligarchy, poverty and all-powerful Prosecutors General have been a permanent feature of life in Bulgaria for the past thirty years.* But this is not what this post is about and I do support the protests.

While following the news coverage of the protests, I was struck by how often migration and exploitation are referenced by the protesters. It’s very common to see people holding signs, or saying things like, “I want to stay here”, “I want the government to resign so that my children don’t have to leave this country”, “I want my children to return”, “I want to have a future in this country” (as a side note, although the words e/im/migration are widely understood in Bulgarian language, they are not commonly used – in everyday speech, people simply refer to leaving (or running away from!), staying in, or returning to the country, or going abroad). These references are so common because the experiences of migration – and exploitation – have become too familiar to too many Bulgarians.

I returned to Bulgaria a few weeks ago to attend to urgent family matters and I got stuck here because of the travel restrictions caused by the pandemic. I continue working from my parents’ house on GAATW’s global and regional work; but as I speak with friends, family and neighbours and follow the local news, I started noticing the ubiquity of stories of migration and exploitation. They’re everywhere, yet I feel like they don’t receive enough attention either within the country or abroad. So I decided to reflect on some of the stories (or rather snippets – see below) that I heard and how they are connected to the protests.

Not long after I arrived, a friend of my parents' asked me to help her son with something and I agreed. On the next day, her son, I’ll call him Nikolay, came over and said he needs to call the UK government to follow up on the financial support he was entitled to due to the coronavirus crisis but hadn't received receive yet. He’s a few years younger than me and had lived in the UK for five years where he worked in various manual labour jobs, most of the time as self-employed. But his English was not great, he said, and that’s why he needed my help.

It was supposed to be a quick and straightforward effort but we ended up calling the UK government hotline five or six times over several days, spending hours listening to the wait music. During this time, Nikolay shared with me various snippets from his migration journey. For example, one time he said that someone had “burnt” him with 3,000 pounds (i.e. had not paid him for a job done) and because he doesn’t speak English, he didn’t know where to report, so he let it go. Another time he told me that he had lived in a cramped house with several other men, all sleeping on the floor, and the owner of the house gave them 50 pounds now and then “instead of paying us for the work we did – just to keep us from starving”. On another day, he said he had gone to the UK because someone had promised him and a few other guys jobs there; they had paid a hefty fee for these jobs but when they got to the UK, there were no jobs and the recruiter couldn’t be found.

I thought to myself “goodness, this is a classical trafficking story” but it seemed completely inappropriate to talk about trafficking, exploitation, victimhood or rights. Nikolay referred to the recruitment process as being cheated and his mother summed up the whole thing as “it was very hard at the beginning”. And “the beginning” simply seemed irrelevant at this point. As Bulgarians like saying, “the important thing is that we’re alive and healthy”.

Nikolay’s story got me thinking about other relatives who had stints abroad. I remembered that one cousin, I’ll call him Peter, had moved irregularly to Italy in 2000 and had also worked in construction and other manual labour jobs. Again, I don’t know the details of his life there, but my mother told me that “it was very hard at the beginning” for him too – he had spent his first days or weeks in Italy sleeping in parks and eating dry bread. One distant aunt had gone to Greece already back in the 1990s to care for old people. Her daughter, who is my age, was a migrant sex worker (or a victim of trafficking – it wasn’t clear) in Greece and Germany.

By virtue of my work I can recognise that these stories refer to what we would term trafficking, exploitation, irregular migration, deceptive recruitment or non-payment of wages. Yet I am more inclined to accept people’s own terminology, which is along the lines of “hardship abroad”, often temporary. After all, Nikolay had done well for himself after the difficulties in the beginning, and had regularly sent money to his mother and his grandparents. With my help, he received his COVID benefits from the UK, which will support him and his mother for a few months. Peter had bought an apartment in Sofia with his savings from working in Italy. My distant aunt has now retired in Greece.

And these are just a few stories that I’ve come to know. Like in other parts of the world, one can “see migration” while driving through villages and small towns in Bulgaria – houses that are bigger and nicer than the neighbouring ones most likely belong to families where at least one family member works abroad. And conversely - houses that look deserted and unkept perhaps belong to people who have left and don't plan to return. Bulgarians abroad (as we are usually called – not emigrants or expats) are the largest source of foreign investment in the country, remitting around 1 billion Euro per year.

The bottom line, and the reason why many people migrate, and in some cases tolerate exploitation, is that “hardship abroad” is better than the hardship in Bulgaria. Because the minimum wage here is 300 Euros a month, the minimum pension is 100 Euros a month, child benefits are 20 Euros a month and available only to the most destitute families, and healthcare involves a lot of out-of-pocket expenses and/or “gifts” to doctors and nurses.

Thirty years of neoliberal economic reforms, erosion of labour rights and decimation of rural livelihoods have prompted large-scale migration to cities and abroad, leaving entire villages empty and small towns like the one where I am now with crumbling infrastructure. Luckily, a growing number of people, including returnee migrants who have seen how democracy and the rule of law function abroad, are refusing to put up with the status quo. They are protesting and demanding ostavka [resignation] and mafiata vun [mafia – out!]. As the sign above shows, they want to remain in Bulgaria and rightly so – migration should be a choice, not a compulsion.

* I protested in 1996/97, “voted with my feet” in 2009, protested again in 2013 and probably in between, and voted in every election – thus my scepticism.