Criminalisation alone cannot end trafficking in persons

Statement by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women to the United Nations Constructive Dialogue on Trafficking in Persons, 1 July 2022, Vienna

Read the statement below or view it read out by Maya Linstrum-Newman, International Advocacy Officer at GAATW.

Essential but excluded: Rights protections for domestic workers are long overdue

Statement by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women on International Domestic Workers Day

Domestic workers make crucial contributions to households and the global economy, yet continue to suffer from multiple vulnerabilities caused by the lack of recognition and respect for their work, inhumane labour migration regimes, rogue recruitment practices, and gender-based discrimination and violence.

Domestic workers make crucial contributions to households and the global economy, yet continue to suffer from multiple vulnerabilities caused by the lack of recognition and respect for their work, inhumane labour migration regimes, rogue recruitment practices, and gender-based discrimination and violence.

On this International Domestic Workers Day, we highlight the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on migrant domestic workers in the past two years and their exclusion from much-needed social protections. We call for measures to improve their working and living conditions as well as access to labour rights and government support.

In our recently published research on reintegration of women migrant (domestic) workers from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka who had returned from the Middle East, the vast majority reported a host of human and labour rights violations but very limited government assistance, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Towards a fair and inclusive society for all

Statement by Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women on International Women’s Day 2022

GAATW stands in solidarity with all women workers – paid and unpaid, local and migrant. We salute their courage to organise, form collectives, and support each other in this difficult time. We are inspired by their creative and innovative organising strategies.

We also applaud the steps taken by some states to provide migrants, including undocumented migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, with various forms of emergency support. Initiatives to extend visa and work permits and to create firewalls between access to services and immigration authorities are stepping stones to creating inclusive societies. More recently, we have been touched by the generosity of neighbouring countries towards people fleeing the war in Ukraine.

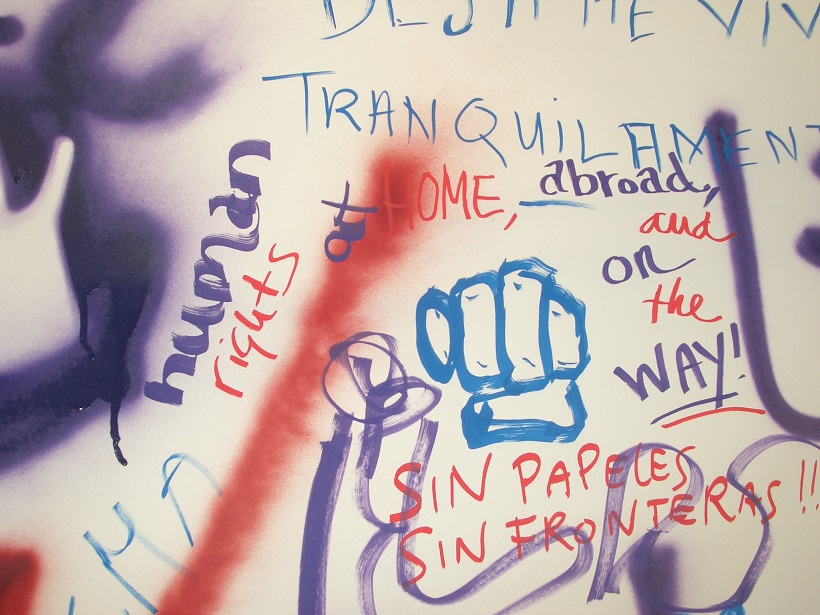

In Agenda 2030, states made commitments to promote the socioeconomic and political inclusion of all, ensure decent work, and end violence against women, among others. As signatories to the Global Compact on Migration, states have also agreed to ensure empowerment and inclusion of migrants and work towards social cohesion. Yet, the exclusion and othering that we have seen in the last two years and, most recently, towards non-Europeans fleeing Ukraine, tell us that reality is very different. Sadly, our states and we as people have many excuses to justify exclusion and rejection of our fellow human beings. Gender, race, class, caste, religion, and ethnicity are invoked in different contexts, both within countries and across borders, to justify exclusion.

Stop all forms of gender-based violence: A manifesto for an inclusive and comprehensive EU gender-based violence policy for all

In the lead up to International Women’s Day, 8 March, and the expected publication of a draft EU law to address violence against women and domestic violence, major international and European networks and organisations have adopted a manifesto for a truly inclusive EU law and policy. All civil society organisations and Members of European Parliament are invited to join us – sign up to the manifesto here.

Strengthening Intersectional Analyses and Responses to Labour Migration

In April, we launched a six-part series titled “Feminist Fridays: Conversations about Labour Migration from a Feminist Lens”, in collaboration with Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), Focus on Labour Exploitation (FLEX), Solidarity Center, and Women in Migration Network (WIMN).

In April, we launched a six-part series titled “Feminist Fridays: Conversations about Labour Migration from a Feminist Lens”, in collaboration with Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), Focus on Labour Exploitation (FLEX), Solidarity Center, and Women in Migration Network (WIMN).

In these sessions, we reflected on how to undertake the complex work of standing in solidarity with migrant workers and celebrating their agency while also highlighting the abuse and exploitation they face. Feminist academics, civil society leaders, and migrant workers themselves discussed how to better understand and represent the lived experiences of migrant workers, especially women, who are overrepresented in low-paid and precarious jobs in the informal sector, and who have absorbed even greater caring responsibilities during the pandemic.

Interview: Tenth Anniversary of Anti-Trafficking Review

GAATW launched Anti-Trafficking Review - the first open access, peer reviewed journal focusing on human trafficking - in 2011. On the occasion of this tenth anniversary, the journal Editor, Borislav Gerasimov, spoke to three of the women who conceptualised and launched the journal and have continued to support it in various capacities: Bandana Pattanaik, International Coordinator of GAATW, Caroline Robinson, who was working at the time as International Advocacy Officer at GAATW, and Rebecca Napier-Moore who was working at the time as Research Officer. Caroline and Rebecca were part of the editorial team for the first issue, and Rebecca continued as journal Editor through 2016.

Voices and Participation of Victims, Survivors and Workers: Reflections on World Day Against Trafficking in Persons

Bandana Pattanaik

Listening to the lived experiences of trafficked persons and incorporating their feedback in anti-trafficking initiatives have always been a practice among many GAATW members. The International Secretariat has also taken a number of steps over the years to ensure that state and non-state actors consult trafficked persons while planning their anti-trafficking work.

Listening to the lived experiences of trafficked persons and incorporating their feedback in anti-trafficking initiatives have always been a practice among many GAATW members. The International Secretariat has also taken a number of steps over the years to ensure that state and non-state actors consult trafficked persons while planning their anti-trafficking work.

However, this is work in progress. While organising survivor-testimony sessions and seeking their input on assistance measures are not difficult, ensuring their participation in all aspects of anti-trafficking work is fraught with many barriers. On this World Day Against Trafficking in Persons, I would like to reflect on our work to centre the voices and concerns of survivors and suggest ways to make it better.

I remember a consultation organised by GAATW, AWHRC (Asian Women’s Human Rights Council), SANGRAM (a sex workers’ support group based in Kolhapur, India) and VAMP (a sex workers’ collective based in Sangli, India) in March 1999. It had brought together organised and individual trafficked persons, organised sex workers, academics and activists from Bangladesh, China, Cambodia, India, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Taiwan.

GAATW Statement at Multi-Stakeholder Hearing on Global Plan of Action

Oral statement by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) for Panel 1 of the UN Multi-stakeholder Hearing on Trafficking in Persons, “The Global Plan of Action and enduring trafficking issues and gaps”, 13 July 2021

Delivered by: María Emilia Cebrián

Madam Vice-President, Distinguished Delegates, Ladies and Gentlemen,

The present statement addresses the following guiding questions, as per suggested in the concept note for the Multi-stakeholder Hearing on Trafficking in Persons:

- How should understanding the root causes of trafficking in persons inform coordinated efforts to respond?

- How can we provide greater international protection and support for survivors of trafficking in persons?

The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) welcomes the recognition by States Parties of human trafficking as a serious crime and a human rights violation, and for their commitment to addressing trafficking through the Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons. In the past two decades, almost every country in the world has introduced legal mechanisms and practical measures to address human trafficking. Yet, we are very far from ending trafficking and exploitation. Therefore, it is imperative for us all now to reflect on the challenges in this work and broaden the scope of anti-trafficking measures.