Bandana Pattanaik

Listening to the lived experiences of trafficked persons and incorporating their feedback in anti-trafficking initiatives have always been a practice among many GAATW members. The International Secretariat has also taken a number of steps over the years to ensure that state and non-state actors consult trafficked persons while planning their anti-trafficking work.

Listening to the lived experiences of trafficked persons and incorporating their feedback in anti-trafficking initiatives have always been a practice among many GAATW members. The International Secretariat has also taken a number of steps over the years to ensure that state and non-state actors consult trafficked persons while planning their anti-trafficking work.

However, this is work in progress. While organising survivor-testimony sessions and seeking their input on assistance measures are not difficult, ensuring their participation in all aspects of anti-trafficking work is fraught with many barriers. On this World Day Against Trafficking in Persons, I would like to reflect on our work to centre the voices and concerns of survivors and suggest ways to make it better.

I remember a consultation organised by GAATW, AWHRC (Asian Women’s Human Rights Council), SANGRAM (a sex workers’ support group based in Kolhapur, India) and VAMP (a sex workers’ collective based in Sangli, India) in March 1999. It had brought together organised and individual trafficked persons, organised sex workers, academics and activists from Bangladesh, China, Cambodia, India, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand and Taiwan.

It was my first international meeting as GAATW staff and the respectful discussion among people who were genuinely trying to understand complex concepts such as choice, consent, and exploitation by listening to lived experiences was truly educative. Colleagues did not always agree with each other. There was vast diversity in terms of class, caste, religion, ideology, language and sexuality. Women who had been rescued from brothels and formed their own survivors’ collective or were staying at shelters shared space with sex workers who were organising for their rights. Academics struggled to find a language that people with no formal education would be able to understand. The discussions made it clear to me that intersectional conversations, however difficult, are the only way to move forward with social justice work. I also learnt that the rights of sex worker and rights of trafficked persons are not mutually exclusive.

This learning was further deepened in a meeting of the erstwhile UN Working Group on Contemporary Forms of Slavery a few months later. The UN Trafficking Protocol was nearing finalisation and the Working Group was reviewing the 1949 Convention. Again, a representative from a sex workers’ collective and a trafficking survivor were speaking at a high-level policy-oriented panel along with human rights activists. The two women had very divergent views on the 1949 Convention. Based on her lived experience with the Indian Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, the sex worker said that the 1949 Convention tramples on their rights. The trafficking survivor from the Philippines, on the other hand, thought that the Convention should be implemented all over the world, if we really want to end human trafficking. Later that evening, some of us had a review of the session in a small group. The sex worker and the trafficking survivor spoke to each other via translation and although they still did not agree on policy matters, each was able to see the other’s point of view.

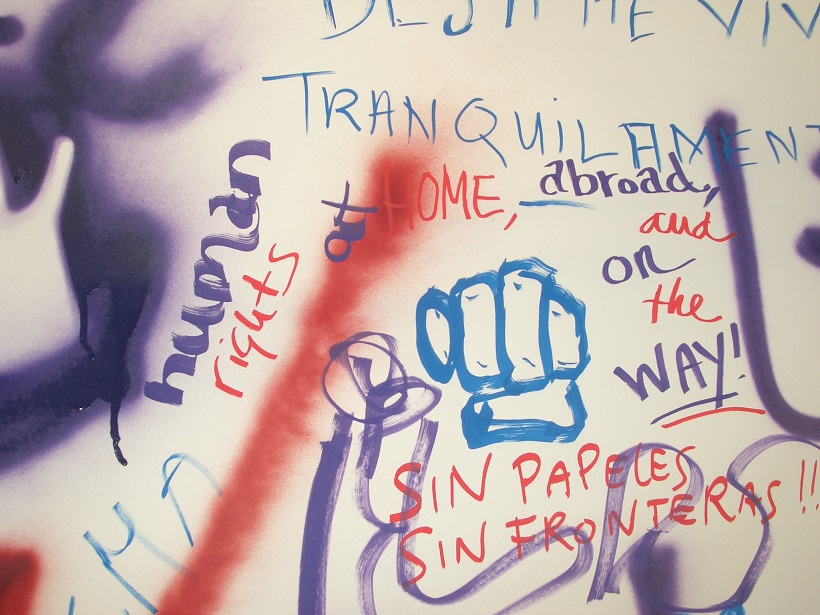

Over the years, GAATW members in Asia, Europe and Latin America have carried out Feminist Participatory Action Researches with victims and survivors to find out the lacunae in their own assistance measures and taken steps to address them. They have also taken steps to hold states accountable to the rights of trafficked persons. Our work with self-organised survivors and workers has created spaces for inter-movement dialogues and strengthened inter-sectoral solidarity beyond multiple borders. Collectives of trafficking survivors such as Shakti Samuha in Nepal and Live our Lives in Thailand are continuing to engage with CSOs and policy makers in their respective countries. Sunita Danuwar, a survivor of child trafficking from Nepal and one of the founding members of Shakti Samuha, and Eni Lestari, a migrant domestic worker leader who is also the Chair of International Migrants Alliance, have served two full terms on GAATW International Board and provided strategic guidance to the Alliance. Atlantas and Samen Sterk from the Netherlands and SEPOM from Thailand are no longer operational but their valuable contribution to the anti-trafficking discourse is recognised. Sex workers collectives such as DMSC, VAMP, EMPOWER, WNU and many others have strengthened their organising by forming national, regional and international alliances. Drawing upon their lived experiences, they have come up with rich and nuanced understanding of human trafficking and raised their voices against exploitation. Domestic workers, contractual garment workers in export-oriented factories, brick kiln workers and many others in the informal economy, both local and migrant, have formed collectives and unionised to speak out against abuse and exploitation, including trafficking.

This year the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights launched the International Survivors of Trafficking Advisory Council (ISTAC), comprising 21 survivors across the OSCE region. ISTAC will advise ODIHR in its anti-trafficking work. Further, UNODC launched a campaign entitled Victims’ Voices Lead the Way. The campaign recognises survivors as key actors in anti-trafficking work and highlights the importance of listening to and learning from them. I am reminded of our advocacy work at the UNODC for a ‘victim-centred review mechanism’ to the UN Protocol more than a decade ago. Members of Samen Sterk and SEPOM had played key roles in that advocacy and we also had participation of survivor leaders from different parts of the world. Perhaps the time has come now for greater involvement of survivors in the monitoring of anti-trafficking initiatives.

Steps taken by ODIHR and UNODC for inclusion of survivors are commendable and should be emulated by others. However, some insights from GAATW’s work in communities across the globe may be important to keep in mind so that our efforts to centre the voices of trafficking survivors in anti-trafficking initiatives do not become tokenistic.

- GAATW’s research and interaction with women who had experienced trafficking shows that while the survivor identity is fine for some, many find it a problematic appendage and a barrier to community reintegration. They actively resist the idea that their identities, needs, abilities and worth could only be based on their trafficking experience – one phase in a very complex and rich life. As Ku-Larp, a member of SEPOM had pointed out, “I received a lot of help from various places, as a trafficking victim, from both the government and NGOs. But if I had the right to choose, I would choose just normal help, without the terms ‘trafficking’ or ‘victim’ being used.” So it is quite likely that some survivors may want to engage in anti-trafficking work without being labelled as such.

- Survivors are best placed to tell policy makers if anti-trafficking measures are adequate and if they are reaching trafficked persons. Based on what we know about the available assistance measures to trafficked persons, in many countries it is a situation of too little, too late for too few. Many people who experience trafficking are either not identified by the authorities or do not want to identify themselves as trafficked because what they need is decent work – not assistance in a shelter or repatriation to their home towns or countries. This is where survivors, precarious workers and social justice activists must join hands for a coordinated demand to change the systems that disenfranchise so many people.

- When a very large number of people do not enjoy their basic rights to health, education, food, and decent work, demanding these rights only as rights of trafficking survivors once again lets states off the hook. The stark irony of a ‘victim-centred approach’ was evident a few years ago when some CSOs in India were applauding a draft Anti-Trafficking Bill and mobilising survivors to congratulate the state for creating mechanisms for institutional care for them. It appeared as if the only way people from disadvantaged communities can demand their rights from the state is by accepting the label of ‘victims’. Instead, urgent steps should be taken so that more and more people are able to enjoy those rights and do not become victims of trafficking or other abuse.

- A scenario where it is possible to realise one’s rights or one’s authenticity only as a ‘victim’ or ‘survivor’ of trafficking is problematic because at the extreme end it encourages victim-scripts and ‘neoliberal sexual humanitarianism’.

- While the human rights gains of anti-trafficking initiatives are nominal, their adverse impact on certain groups of people such as sex workers and working-class migrants have been well-documented by GAATW and others. Yet sections of civil society and policy makers remain divided over their position on sex work and migration. It is imperative, therefore, that international organisations such as ODIHR remain above these ideological divides and ensure inclusion of pro-sex workers’ rights survivors in ISTAC. Our member ICRSE has raised this issue and we strongly reiterate their demand.

Finally, two decades after the UN Protocol and despite its popularity among state and non-state actors, it is clear that the problems of trafficking cannot be addressed by anti-trafficking measures alone. If we would like survivor leaders to engage in efforts to end trafficking and exploitation, we need to ensure that they have a grounded and critical understanding of the socio-political and economic paradigm that creates and maintains inequality, exploitation and injustice. An individual’s, in this case, a trafficked person’s, lived experience is valuable, precious and unique. But lived experiences by themselves do not enable us to analyse the factors which create those experiences.

While some people in the anti-trafficking community have done commendable work to ensure that victims recover from physical and psychological trauma and rebuild their lives, not much has been done to enable them to analyse their lived experiences against the backdrop of their macro-level realities. Political education and critical literacy of trafficking victims are not part of any assistance programmes. Nor are they part of mainstream educational curriculum and pedagogy in most countries. However, that is what all of us, including the survivors; need in order to continue our work for social change.