Can Anti-Trafficking Measures Stop Trafficking?

By Bandana Pattanaik

It was early 2000. My colleagues from GAATW International Secretariat and I were in a small village in Battambang province of Cambodia. With us were colleagues from Cambodia Women’s Development Agency (CWDA), one of our member organisations from the country. Our Feminist Participatory Action Research project focussing on Cambodia and Vietnam had reached its ‘Action’ phase and the community researchers were taking us to meet some of the trafficked women who participated in the research. One of the ‘Actions’ was providing ‘Assistance’ to trafficked women. Most of the women had chosen to start small businesses and a few had opted to return to school. The women we spoke to were enthusiastic and hopeful that their future life would be better than what they had experienced in the past. They talked about their fear and excitement about returning to school as older students. They discussed the challenges of running a little noodle shop or a small salon in their locality and how they must be careful about family using up all their profits.

It was early 2000. My colleagues from GAATW International Secretariat and I were in a small village in Battambang province of Cambodia. With us were colleagues from Cambodia Women’s Development Agency (CWDA), one of our member organisations from the country. Our Feminist Participatory Action Research project focussing on Cambodia and Vietnam had reached its ‘Action’ phase and the community researchers were taking us to meet some of the trafficked women who participated in the research. One of the ‘Actions’ was providing ‘Assistance’ to trafficked women. Most of the women had chosen to start small businesses and a few had opted to return to school. The women we spoke to were enthusiastic and hopeful that their future life would be better than what they had experienced in the past. They talked about their fear and excitement about returning to school as older students. They discussed the challenges of running a little noodle shop or a small salon in their locality and how they must be careful about family using up all their profits.

One young woman, let’s call her Kanya, was the most talkative person in the group. She was overjoyed about having been able to return to school. She was happy that she looked younger than her real age and did not attract much curiosity from her younger classmates. Kanya tried out her few sentences in English on me and was thrilled when she understood my reply.

Anti-trafficking, Policing, and State Violence

Jennifer Suchland, Associate Professor, Ohio State University, Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies,

What is the relationship between policing, state violence and anti-trafficking? That is the question we should double-down on at this historical moment, as global outrage and protesting demand justice for the Black lives killed by racist police. There is a deep and serious connection between anti-trafficking strategies and systems of oppression and violence endemic to policing, border control, prisons, detention centers, and surveillance. These systems are sources of violence that remain at the center of the anti-trafficking apparatus because human trafficking is primarily understood and approached as a problem of criminal justice. While countless activists and scholars have exposed these connections, the most dominant approaches to anti-trafficking still actively align or are complicit with systems of injustice such over-policing, deportation, and mass incarceration.

What is the relationship between policing, state violence and anti-trafficking? That is the question we should double-down on at this historical moment, as global outrage and protesting demand justice for the Black lives killed by racist police. There is a deep and serious connection between anti-trafficking strategies and systems of oppression and violence endemic to policing, border control, prisons, detention centers, and surveillance. These systems are sources of violence that remain at the center of the anti-trafficking apparatus because human trafficking is primarily understood and approached as a problem of criminal justice. While countless activists and scholars have exposed these connections, the most dominant approaches to anti-trafficking still actively align or are complicit with systems of injustice such over-policing, deportation, and mass incarceration.

At this moment, some anti-trafficking organizations and advocates have denounced racism but have not taken a hard look at how their work may implicitly support racist, anti-migrant, heteropatriarchal policing. Playing on the widespread public sympathy for “modern day slavery,” anti-trafficking advocates often validate and reinforce policing and criminal justice institutions. For example, in my local context of Columbus, Ohio, Mayor Andrew Ginther highlighted the Police and Community Together Team (PACT), a special force created to address human trafficking, as the main positive example of community policing in his first public response to the mass protesting against police violence here.

The Situation of Sex Workers in Norway During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Astrid Renland, PION, 4 May 2020

The Covid-19 pandemic has hit people engaged with sex work in Norway extremely hard both due to the lack of income and other financial problems, as well as the shutting down of health and social services for people selling sex. Whilst the government has established and provided crisis support for industry, businesses, workers, freelancers, self-employed people and so on, sex workers have not been offered any help. Except for the offer from some municipalities to cover their expenses to leave the country.

In the last months, PION has established a crisis fund helping sex workers with money for food and basic needs while the health and social service providers support those who are in need with food and other help via digital contacts.

In addition, sex workers must deal with the COVID-19 pandemic in an already hostile and repressive political environment caused by the increasing criminalisation and conflation of sex work, migration and human trafficking in the first decade of 2000 which led to the ban on purchasing sex in 2009.

Women, Work and Migration: Community-led initiatives in Chhatisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha

Namrata Daniel, 25 March 2020

In February, GAATW organised a meeting ‘Women, work & migration: community-led initiatives in Chhatisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha’. It took place in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, with representatives from seven civil society organisations that work with women and marginalised communities in the three states. The purpose was to discuss and understand the structural factors that cause the inter-state labour migration of women from these three origin states.

The discussions were focussed on developing a holistic approach to human trafficking and labour migration issues through community-led initiatives. The aim of this work is not to stop the workers from migrating, but instead to identify the structural drivers pushing them to migrate and the ways in which we can empower local communities and create better livelihood options for them. With a strong community work and engagement with the workers, the aim is to improve the economic conditions of the community, for example, by focussing on the implementation of government schemes and programmes on livelihood generation, education, health care, child care etc. The community work should ensure better linkages between different government schemes for empowerment of local communities and especially women workers.

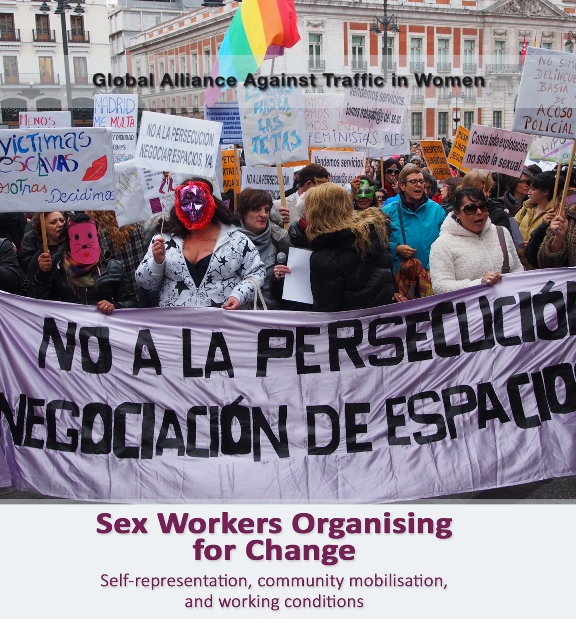

Sex workers can tell you why sex work is work. Speak to them.

Borislav Gerasimov, 21 January 2020

A slightly modified version of this blog first appeared on Beyond Trafficking and Slavery

The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) was founded in 1994 by a group of feminists and women’s rights advocates from, mostly, the Global South. As students, activists, asylum seekers, or migrants in the Global North, they had witnessed the struggles of their compatriots with much less privilege than their own. And as volunteer caregivers, translators, interviewers, and advocates in law courts, GAATW’s founding mothers had heard the stories of working-class migrant women who had undertaken journeys in search of better livelihoods.

Typically, women narrated stories of difficult situations: of the broken promises of agents/recruiters, unbearable working conditions, and financial destitution. Their stories, hard as they were to hear, testified to the women’s courage, enterprise, and determination and challenged the stereotype of ‘the victim of trafficking’ prevailing in the Global North.

El festín durante COVID-19: El movimiento contra la trata debe dar un paso atrás

Hace unas dos semanas, a mediados de marzo, una de nuestras colegas recibió un mensaje de una periodista tailandésa que preguntaba: “¿Crees que las trabajadoras sexuales serán más vulnerables a la trata ahora que el gobierno de Tailandia ordenó el cierre de todos los lugares de entretenimiento?”. En nuestro grupo de WhatsApp de la oficina, bromeamos: “Bueno, esto (la conexión entre COVID-19 y la trata) no tomó mucho tiempo”.

Y teníamos razón. Desde entonces, hemos visto muchos artículos, blogs y comentarios sobre cómo la pandemia actual y sus consecuencias implicarán un mayor riesgo de trata y “esclavitud moderna”. Para ser claros: sin duda lo harán. No es necesario resumir las noticias de las que todas y todos somos tristemente conscientes, que muestran cómo la mayor parte de la fuerza de trabajo del mundo (básicamente, cualquiera que no tenga todo esto: computadora, casa y un contrato de trabajo que le permita trabajar desde su casa en dicha computadora - y/o ahorros) se queda sin sus ingresos regulares. O cómo la falta de ingresos y redes de seguridad social empujan a las personas a aceptar acuerdos laborales en condiciones de explotación.

Sin embargo, de alguna manera se siente poco sincero preocuparse por la trata de personas en este momento. Consideremos esta cita de un trabajador jornalero en India, publicada en The Guardian: “Si el Coronavirus no me mata, el hambre lo hará”.

Women and Violence in the World of Work

GAATW has long engaged with the issue of women's rights to mobility and work, and sees trafficking as an outcome of structural inequalities and a form of violence that undermines their enjoyment of these rights. We see and seek to support women workers organising and collectivising to tackle trafficking and other forms or exploitation. In our current work, we highlight stories of resistance of individuals and collectives in the process to raise awareness about the importance of organising, demonstrating and building solidarity among women workers. Working with different contributors from the media and workers’ rights organisations, we feature stories on gender-based violence in South Asia. We are focusing on supporting the rights of women (migrant) domestic workers, agricultural workers, and garment workers to organise and encourage collective bargaining with a view to ending both the structural violence and physical, psychological violence and harassment they experience in their everyday lives.