At the end of January...

This is the first in what we hope will become a series in 2021 where we share information and opinions on some of the previous month's events that are relevant to GAATW members and partners.

Bandana Pattanaik

The first month of 2021 has ended and what a month has it been! The pandemic still keeps us under its control and many countries are dealing with a ‘second wave’ now. However, those of us fortunate to have our jobs, have also learnt to adapt to working from home and communicating remotely with colleagues, friends and sometimes with family too. In terms of in-person meetings, community interaction, international conferences and large meetings, this year is not looking very different from the last.

‘Vaccine Nationalism’ does not (even) make economic sense

Vaccination programmes have started in many countries but the competition and hoarding that we witness is worrying. Covax, the pooled procurement scheme, has been set up and many wealthy countries have signed up to support it but they have also placed their own direct orders with the pharmaceutical companies which has effectively pushed Covax towards the end of the queue. International cooperation on vaccine distribution is necessary for everyone’s safety and global economic recovery. According to recent research, ‘it would cost $25 billion to supply lower income countries with vaccines. The US, the UK, the EU and other high-income countries combined could lose about $119 billion a year if the poorest countries are denied a supply. If these high-income countries paid for the supply of vaccines, there could be a benefit-to-cost ratio of 4.8 to 1. For every $1 spent, high-income countries would get back about $4.8.’

In Managing Migration, are we Prioritising Migrants?

Alfie Gordo, 17 December 2020

The Philippines is among the top ten origin countries and the one with the largest diaspora population. Migration for labour has been a part of almost every Filipino family’s life for decades. Described as an indispensable sector of the Philippine economy, the Philippine diaspora has in many ways become a permanent feature of the country’s GDP through a steady inflow of remittances from Filipino migrant workers.

In 1974, the Marcos administration institutionalised a policy for labour export as a temporary stop-gap measure to impede the rising unemployment rate and severe balance-of-payment pressures.. Nearly five decades and six administrations later, the number of Filipinos leaving the country for work continues to grow steadily due to the government’s effort to diversify its labour markets and to send more Filipino workers abroad.

The once temporary labour programme had become a permanent pillar of life in the Philippines. On the one hand, the country receives commendations for its comprehensive policies and protection measures for Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). On the other hand, labour and migrant rights groups are questioning the government’s overreliance on the labour export programme to stimulate growth in the economy while there is lack of sustainable programmes to provide employment and livelihood opportunities in the country thus making migration a means for survival and a necessity rather than a choice.

Between Borders

Maggi Quadrini

|

|

Although Thiri got to keep her job in Mae Sot, she now struggles with her limited access to healthcare after she developed a waterborne disease during the pandemic. (Image: Linn Let Arkar)

|

Three women working at a garment factory along the Thai-Burma border share their struggles and triumph living away from loved ones amid the COVID-19 pandemic

When 24-year old Chit Ban Wah heard that Thailand was closing its borders as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in mid-March, she and her older sister, both operators at Top Form Brassiere Company Limited garment factory in the border town of Mae Sot, prepared to return to Burma. While in the taxi, she received a call from her employer asking her to stay.

“They told me if I leave, it will be very difficult to come back,” says Chit Ban Wah. “They also told me that if I left I would lose my job.”

Before Chit Ban Wah moved to Mae Sot in 2019 she worked selling cellphones in Burma, earning approximately 6,000 Thai Baht per month (190 USD). She now earns between 8,000 and 12,000 Thai Baht (257 USD – 385 USD) per month, the majority of which she combines with her sister’s salary to send home to their family in the bordering Burmese town of Myawaddy.

“I realized if I left to go home, there would be no more money coming in for my family,” says Chit Ban Wah.

Que le hace falta a la lucha contra la Trata de personas desde la perspectiva de una ONG de Colombia

Bianca Fidone y Betty Pedraza, Corporación Espacios de Mujer

28 de octubre de 2020

Hace poco más de dos meses, en el universo de notas y enunciados publicados con ocasión del Día Mundial contra la Trata de Personas (30 de julio), me encontré con un interesante artículo sobre los ratos, retos, ritos, rotos y rutas de la lucha contra la Trata. Me pareció curioso este título porque jugaba con el cambio de la vocal en una misma palabra para referirse a la situación de la Trata de Personas en Colombia desde diferentes perspectivas.

Leyendo sobre esta grave violación de los derechos humanos, penalmente castigada en Colombia por el artículo 188 A del Código Penal, me di cuenta que, finalmente, las enunciaciones expuestas no eran de exclusiva pertenencia al contexto colombiano, sino que se podían adaptar también a otras realidades.

- RA-tos: La lucha contra la Trata de Personas, desde cualquier ángulo en que se aborde (prevención, asistencia y protección de las víctimas, persecución y judicialización, cooperación internacional, gestión del conocimiento) debe ser permanente y no esporádica, no puede ser solo por ratos o momentos. Cada día, muchos hombres, mujeres, niños, niñas y adolescentes caen en las manos de traficantes, en sus propios países y en el extranjero, así que el combate de esta práctica necesita continuidad y poder decisional, definición de tareas específicas para las instituciones, las estructuras involucradas y las operaciones en terreno. Hablar de Trata de Personas en el Día Internacional a ella dedicada, indudablemente permite una mayor sensibilización y llama la atención de los medios de comunicación sobre un problema “irresuelto” que exige la puesta en marcha de medidas políticas concretas; sin embargo, este tema debe ser importante durante todos los días del año.

Lack of Voter Education in Migrant Communities Driving Electoral Inequality Along Thai-Burma Border

Maggi Quadrini

Sayama Jasmine, a teacher from Yangon, Burma moved to the border town of Mae Sot, Thailand in 1994 when she was 26 years old. Now, nearly 30 years later she is closely watching Burma’s 2020 general election, set to take place on 8 November 2020. She’s never voted, but says she would if she knew how.

Sayama Jasmine is one of approximately 3 million migrant workers from Burma living in Thailand with at least 50,000 in Mae Sot alone. Many of those working in thecountryrepresent different ethnic groups who crossed the border at different periods to flee conflict or to pursue economic opportunities, with the hopes of improving their livelihood. As a teacher, Sayama Jasmine provides Burmese lessons to children living in her neighbourhood. Her self-run school started with just a few students coming over in the evenings to study in her humble, wooden home, surrounded with posters displaying the alphabet and vocabulary. Sometimes, she says proudly,there are up to50 children at one time sitting in the small, modest space.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, she was returning to Yangon every two years to visit her friends and family. Since Thailand closed its borders in March, she has been following Burma’s election through various news sources, predominantly by listening to BBC in Burmese.

Pass the Mic: A Radio DJ Turned Video Producer Amid COVID-19

Maggi Quadrini

When COVID-19 lockdown measures in Thailand went into effect in March 2020, radio DJ Kaung Tip wasn’t able to go and broadcast her program at the recording station in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai.

Before the pandemic started spreading across the globe, Kaung Tip hosted a radio program on women and children’s health called “Heng Jai Ying” (Girl's Power), with the goal of informing her audience of Shan migrants about good health practices and the importance of maintaining good hygiene.

The Shan are an ethnic minority in east-central Burma. Although they share similar language and traditions to populations in northern Thailand, they’re a particularly marginalized group that have long suffered from systematic oppression from the Burma army, known as the Tatmadaw. In 1994, the military led a widespread offensive against the Shan in a scorched earth campaign that pushed over 300,000 people to flee their homes. Thousands of Shan people have been living and working in northern Thailand as migrants since then.

Before the pandemic, “Heng Jai Ying” was broadcasting four days a week. After it became clear that COVID-19 measures would keep her from speaking on air, Kaung Tip had to get creative fast, as thousands of listeners, Shan women in particular, relied on her voice. Seizing an opportunity to change the way Shan migrant listeners engage with the radio program, she began creating short videos that could be easily shared on social media.

Migration, Exploitation, and Pro-Democracy Protests in Bulgaria

Borislav Gerasimov

|

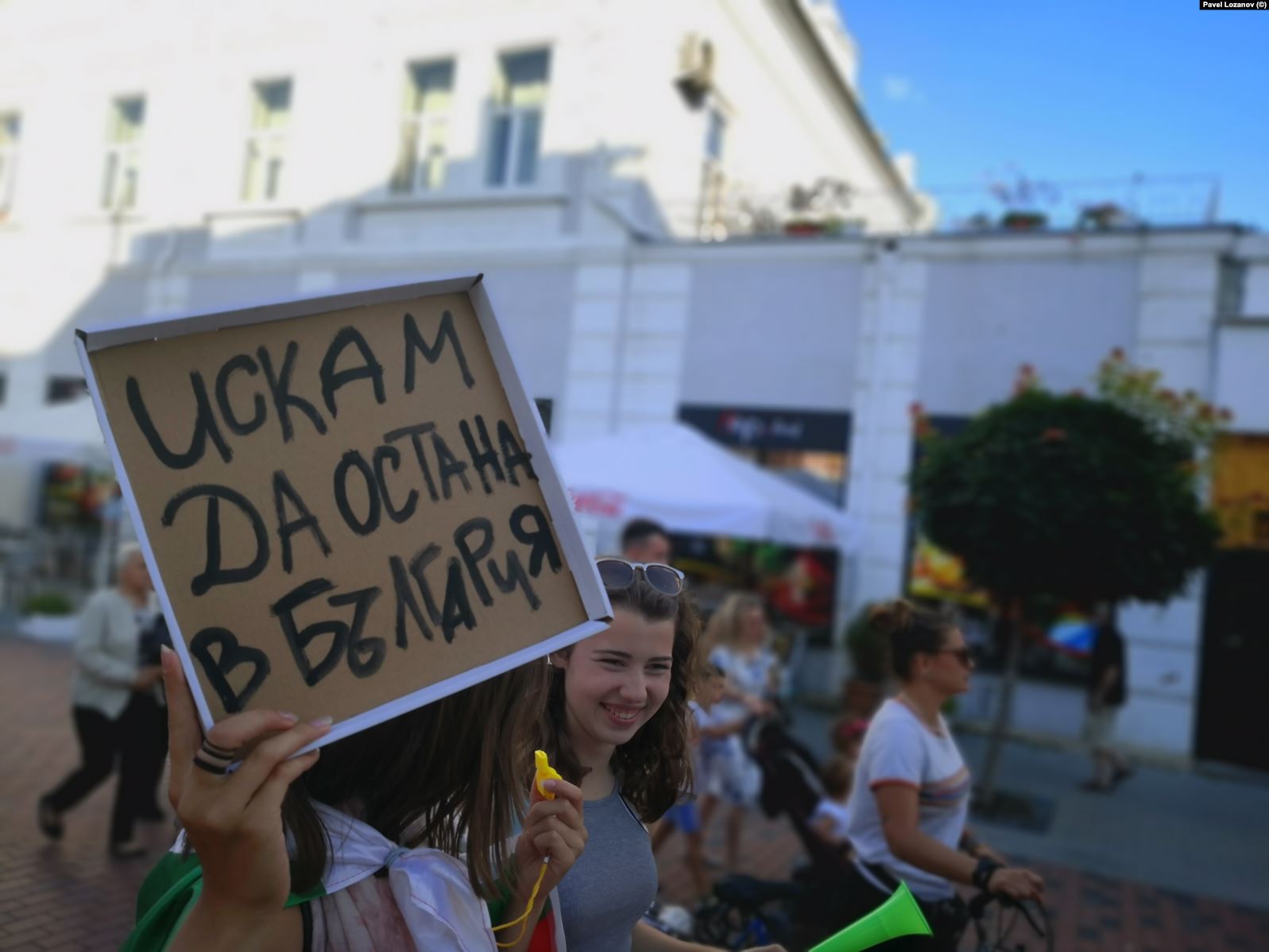

| (A young woman carries a sign that reads “I want to stay in Bulgaria” during a protest in Varna, 14 July 2020. Image: Pavel Lozanov / Svobodna Evropa) |

Bulgaria has been rocked by massive protests since early July, with tens of thousands of people out on the streets demanding the resignation of the Government and the Prosecutor General. People are angry about the wide-spread corruption and the increasing concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small oligarchy while one-fifth of the population lives below the poverty line. Personally, I don’t think the Government’s resignation will bring about the desired change – protests, oligarchy, poverty and all-powerful Prosecutors General have been a permanent feature of life in Bulgaria for the past thirty years.* But this is not what this post is about and I do support the protests.

While following the news coverage of the protests, I was struck by how often migration and exploitation are referenced by the protesters. It’s very common to see people holding signs, or saying things like, “I want to stay here”, “I want the government to resign so that my children don’t have to leave this country”, “I want my children to return”, “I want to have a future in this country” (as a side note, although the words e/im/migration are widely understood in Bulgarian language, they are not commonly used – in everyday speech, people simply refer to leaving (or running away from!), staying in, or returning to the country, or going abroad). These references are so common because the experiences of migration – and exploitation – have become too familiar to too many Bulgarians.

Will Human Trafficking Increase during and after COVID-19?

Bandana Pattanaik

Over the last five months, many reports and statements have alerted us about a possible rise in human trafficking during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. As we discussed this in some detail in a webinar hosted by the ILO last week and had released a statement on the topic earlier this year, I thought of doing a companion piece to my last week’s blog. My intention in going back to the same theme is to start an honest discussion with like-minded colleagues so that together we can take steps to turn this challenging time into a transformative one.

Over the last five months, many reports and statements have alerted us about a possible rise in human trafficking during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. As we discussed this in some detail in a webinar hosted by the ILO last week and had released a statement on the topic earlier this year, I thought of doing a companion piece to my last week’s blog. My intention in going back to the same theme is to start an honest discussion with like-minded colleagues so that together we can take steps to turn this challenging time into a transformative one.

Some of the reports that talk about the possibility of a rise in trafficking cases during and after COVID-19 are very nuanced and cautious. They often start with disclaimers that it will not be possible at this stage to assess the impact of the pandemic on human trafficking. The authors go on to share data on the disruptions in assistance measures to trafficked persons during lockdown periods, inadequate healthcare for victims and caregivers in shelters, challenges of online counselling and delay in court proceedings and repatriation plans. These reports also detail the multiple vulnerabilities faced by migrant workers and those in the informal economy and argue that the impending global economic downturn will lessen people’s capacity to resist exploitation, including human trafficking.